Wal-Mart’s announcement that it is urging its thousands of U.S. suppliers to curb the use of antibiotics in farm animals shines a light on a practice that the meat industry would rather not discuss: the use of drugs on the meat that we eat.

80% of the antibiotics used in the U.S. are used on the animals we eat: injected into them, fed to them and many of the drugs are banned or restricted around the world.

As Wal-Mart steps into this issue, it brings to light one of the most controversial drugs in our food system: ractopamine.

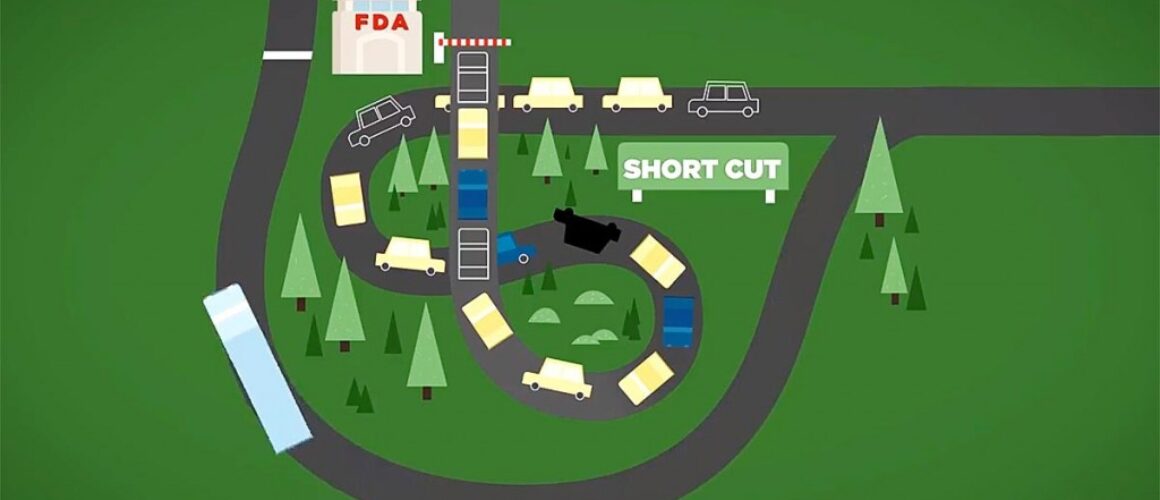

Here in the US, the FDA approved ractopamine and allows the drug to be used widely in U.S. factory farm operations.

There are 196 countries in the world, and it is estimated that 160 countries them ban or restrict ractopamine. But the US? We are not one of them.

The U.K., China, Russia, Taiwan and the European Union ban or limit the use of ractopamine, a drug that promotes growth in pigs, cattle and turkeys. Ractopamine is linked with serious health and behavioral problems in animals, and human studies are limited but evoke concerns, according to the Center for Food Safety.

The U.S. meat industry uses ractopamine to accelerate weight gain and promote feed efficiency and leanness in pigs, cattle, and turkeys. The drug mimics stress hormones.

So how did this drug wind up in our food supply?

The FDA’s approval of the drug relied primarily on the drug-makers’ studies.

No problem, right? Who else would have access to that kind of proprietary information. But if you think about it, it’s kind of like the tobacco industry telling us that we didn’t need to worry about cigarettes. Industry-funded science tends to favor industry.

So what does independent research tell us?

Fed to an estimated 60 to 80 percent of pigs in the U.S. meat industry, ractopamine use has resulted in more reports of sickened or dead pigs than any other livestock drug on the market. According to FDA’s own calculations, more pigs have been adversely affected by ractopamine than by any other animal drug—more than 160,000.

So what exactly does this drug do to the animals that we are eating?

Ractopamine’s effects include toxicity and other exposure risks, such as behavioral changes and cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, reproductive and endocrine problems. It is also associated with high stress levels in animals, “downer” or lame animals, hyperactivity, broken limbs and death.

Based on a lack of available evidence of ractopamine’s safety, most countries have taken a cautionary approach to the presence of ractopamine in their national food systems.

In other words, with the jury still out, they have opted out.

Currently, it is estimated that 160 countries of the 196 in the world ban or restrict ractopamine.

Other countries seem to understand the importance of exercising precaution for stakeholders while the emphasis in our food system tends to focus on the importance of return to shareholders.

While our shareholder-focused food system may have worked for the last twenty years, with the landscape of health changing so dramatically, perhaps it’s time to examine consider the liability it now presents to stakeholders.

The twenty-seven European Union member states, for example, have banned ractopamine. Taiwan severely restricts it.

Russia has announced a ban of imported beef, pork and turkey that is not certified ractopamine-free, and China announced it would stop importing U.S. pork effective March 1, 2013 unless it is certified ractopamine-free by a third party.

As if that isn’t bad enough, while we are eating it, the U.S. has a certified ractopamine-free program in place to sell pork products to the E.U.

In other words, to meet this drug-free demand in other countries, we certify ractopamine-free meat for eaters in other countries, but we just aren’t yet doing it here.

According to the Center for Food Safety, “the U.S. argues that international bans on ractopamine are not based on scientific reasons, but are based on protectionist approaches to enable China, the E.U., and other countries to obtain greater market share. What the U.S. fails to acknowledge is that other countries are taking the lack of human health and animal welfare studies very seriously; ractopamine has not been conclusively determined as safe for humans and animals.”

While few consumers are aware of ractopamine’s use in meat production, the drug has been at the center of international trade disputes for several years, reported NBC News.

It’s not the first time that we’ve seen this, with other ingredients like genetically engineered organisms recently added to our food supply, those long-term human health studies flat out don’t exist. So the industry can conclude “no evidence of harm.” But that’s not the same thing as “evidence of no harm” which is why most countries either ban or label a lot of these new ingredients. It’s called the precautionary principal.

In light of the escalating rates of diseases in the United States and the concern over antibiotic resistance we are now seeing, isn’t it time to ask: What price are we paying for a meat supply so hopped up on drugs? And isn’t it time to join the 160 other countries around the world and begin to do something about it?

Smithfield, one of the largest U.S. pork producers, has at least one production plant that is 100% ractopamine-free and was expected to have its largest plant 100% ractopamine-free by March 1, 2013. These two plants likely service Smithfield’s E.U. and Chinese customers. However, Smithfield said that it will continue to produce pork with ractopamine for other customers. This means Americans. But in a twist, an Asian meat giant struck a $4.7 billion deal and acquired the Virginia based company in September 2013, according to the Wall Street Journal.

So while China makes acquisitions to ensure that its pork supply is free of ractopamine and public interest groups sue the FDA, demanding records of this controversial drug, consumers have a choice: to simply eat less meat or to purchase organic meat, which by law is not allowed to use this drug in production, until our own American corporations decide to make our meat ractopamine-free here in the United States, too.

As Wal-Mart steps into this issue, it’s time for other companies to follow. It’s time to build a food system that meets the needs of 21st century consumers, not just the corporations feeding them.