Science for Sale? The Funding Behind the Latest Study on Peanut Allergy

Written in memory of Chandler, Casey, Sabrina, Emily, Giovanni, Joseph, Connor and all of the other lives lost to a peanut allergy.

The New England Journal of Medicine’s recently published a five year study where peanuts introduced to the diet of infants reduced the incidence of developing peanut allergy by age 5 by 80%.

The study had hit like a grenade in the food allergy world and triggered an allergic reaction in parents.

Why?

The study threw out 10% of at-risk babies before it even started and was funded in part by the peanut industry, but this was not highlighted in the media.

That’s like conducting a diabetes study on sugar, funded by the sugar industry, but not mentioning it.

Nowhere in the New England Journal of Medicine editorial, “Preventing Peanut Allergy through Early Consumption — Ready for Prime Time?”did the authors share this critical statement: “The National Peanut Board is providing funding to support this research.” Nowhere in the press was it shared. Given how prevalent the peanut allergy has become, parental instinct kicked in, and the reaction was strong.

From 1997-2010, the prevalence of peanut allergy in children has more than quadrupled in the United States.

Today, a food allergy reaction sends someone to the emergency room once every three minutes. The vigilance, stress and lost lives associated with this condition are impacting families, schools and communities around the country.

Parents are asking: Why is this? And the scientific community is trying to wrap its head around it, too. More science is absolutely critical.

According to a new study funded in part by the peanut industry, it may be because we don’t feed our babies enough peanuts.

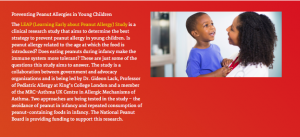

Known as the LEAP (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy) Study, the study is a clinical research study that aims to determine the best strategy to prevent peanut allergy in young children

The study aimed to find out: Is peanut allergy related to the age at which the food is introduced?

The New England Journal of Medicine grabbed headlines with an article: “Preventing Peanut Allergy through Early Consumption — Ready for Prime Time?”

Authored by Rebecca S. Gruchalla, M.D., Ph.D., and Hugh A. Sampson, M.D.T, “the trial was designed to examine two groups — children who had negative results on the peanut skin-prick test at enrollment (nonsensitized) and those who had “mild” sensitization at enrollment (wheals with mean diameters of 1 to 4 mm in response to the test).” Its conclusion was widely touted: “Early consumption was effective not only in high-risk infants who showed no indication of peanut sensitivity at study entry (primary prevention) but also in infants who had slight peanut sensitivity (secondary prevention).”

But the media attention on the study and the doctors writing the editorial for the New England Journal of Medicine failed to highlight two things:

- The study was funded in part by the National Peanut Board.

- A skin-prick test, administered to the infants prior to the study, resulted in 10% of infants being removed from the trial because of the potential for a life-threatening allergic reaction.

That’s like conducting a diabetes study on sugar and throwing out the diabetics before you start. It skews the results, when if the food had been given to the entire population, without pre-screening, the results would have been entirely different. Of course these children had to be omitted from the study, no ethics board would approve of putting those babies at risk, but the omission was not highlighted in the headlines, putting other infants at risk.

At the conclusion of the New England Journal of Medicine article, the authors write:

“We believe that because the results of this trial are so compelling, and the problem of the increasing prevalence of peanut allergy so alarming, new guidelines should be forthcoming very soon.”

Now imagine if a well-meaning caregiver simply reads the headlines and thinks to give a child peanuts to prevent peanut allergies. Imagine if a food company decides, based on headlines, to develop a product line for infants, to expose them to peanuts?

Would they have known that 10% of children tested reacted so strongly to the peanut that they were disqualified from the trial before it even began? Would they know to have given a skin-prick test as the authors advised before introducing the peanut? Would they have known that the study was funded by the peanut industry as stated in the last sentence captured in the adjacent image?

Would they have known that 10% of children tested reacted so strongly to the peanut that they were disqualified from the trial before it even began? Would they know to have given a skin-prick test as the authors advised before introducing the peanut? Would they have known that the study was funded by the peanut industry as stated in the last sentence captured in the adjacent image?

The peanut industry funding was not mentioned in the New England Journal of Medicine article by the researchers, Hugh Sampson, MD Rebecca S. Gruchalla, M.D., Ph.D. It would be an easy addition.

Food allergies have been skyrocketing in the United States in the last fifteen years. Not only has the Centers for Disease Control reported a 265% increase in the rates of hospitalizations related to food allergic reactions in a ten year period, but the sales of EpiPens, a life-saving medical device for those with food allergies, has also seen record sales growth according to the New York Times.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, living in the United States for a decade or more may raise the risk of some allergies.So how does this stack up to other countries?

“Children born outside the United States had significantly lower prevalence of any allergic diseases (20.3%) than those born in the United States (34.5%),” said a study led by Jonathan Silverberg of St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York.

Let’s restate that:

Children born in the US have more than a 1 in 3 chance of having allergic diseases like food allergies, asthma or eczema, while kids born in other countries around the world had a “significantly lower prevalence” of 1 in 5.

On top of that, “foreign-born Americans develop increased risk for allergic disease with prolonged residence in the United States,” the study.

According to Reuters and Dr. Ruchi Gupta, who studies allergies at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago but wasn’t involved in the new research, “This is definitely something we see clinically and we’re trying to better understand, what is it in our environment that’s increasing the risk of allergic disease?”

“Food allergies have increased tremendously,” she told Reuters Health. “We do see people who come from other countries don’t tend to have it.”

And while companies like Allergen Research Corporation secure series A financing rounds, led by Longitude Capital, raising nearly $17 million, including support from Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE), the nation’s leading nonprofit focused on food allergies, to create synthetic peanuts, the real issue remains:

In the United States alone, the prevalence of the peanut allergy has more than quadrupled in the past 13 years. Peanut allergy has become the leading cause of anaphylaxis and death related to food allergy in the United States, and the only way to protect these children is to avoid the peanut.

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that parents refrain from feeding peanuts to infants at risk for the development of atopic disease until the children reached 3 years of age. In 2008, that position was quietly rescinded.

Sales from Mylan’s specialty unit, which is composed primarily of the EpiPen injector used for allergic reactions, increased 29 percent to $462 million, with EpiPen on track to record $1 billion in sales in 2014, which would be Mylan’s biggest single product and its first blockbuster drug.

The bottom line is that this epidemic has come on so hard and so fast that we are still trying to understand what is triggering it. There is not a parent or person on the planet who would choose to have this condition. We need more science, but it must be responsibly presented in the media.

In the meantime, here is the data:

- From 1997-2010, the rate of the prevalence of the peanut allergy in the United States more than quadrupled.

- 10% of U.S. infants now test positive to a skin-prick test for the peanut allergy

- Doctors are not always disclosing industry ties.

- Children born in the U.S. have more than a 1 in 3 chance of having allergic diseases like food allergies, asthma or eczema, while kids born in other countries had a “significantly lower prevalence” of 1 in 5

- A food allergy reaction sends someone to the emergency room once every three minutes in the United States

If the food industry is interested in developing products to meet the changing needs of 21st century families, reduce their risk of liability and protect shareholder return, their best bet is to speak directly with consumers. It will give them insight into the changing needs of the 21st century.

The landscape of health has changed, and it is changing the landscape of food.

In no way is this meant to dismiss the actual study. The concerns center around the fact that the New England Journal of Medicine’s editorial did not disclose the National Peanut Board funding and how the article was handled in the press. The more science we can have on this issue, the better for everyone involved.

Clarifying Note: The references to the New England Journal of Medicine in this article are to the editorial titled “Preventing Peanut Allergy through Early Consumption — Ready for Prime Time?” which did not mention the National Peanut Board involvement. The involvement is disclosed in the study itself as see here.

Sources:

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMe1500186

http://snacksafely.com/2015/02/of-babies-peanuts-and-allergy-moms/

http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/04/29/us-born-kids-allergies-idUSBRE93S0VP20130429

http://triblive.com/business/headlines/7047861-74/quarter-mylan-share#axzz3TpyYxEuF

http://www.nejm.org/doi/suppl/10.1056/NEJMe1500186/suppl_file/nejme1500186_disclosures.pdf

http://patents.justia.com/inventor/hugh-sampson?page=2