Science for Sale: How the EPA Deliberately Ignored Glyphosate Toxicity

A new analysis from the peer-reviewed scientific journal Environmental Sciences Europe documents the diametrically different approaches the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the World Health Organization took when determining the cancer risk from exposure to Monsanto’s weedkiller glyphosate.

A new analysis and report shows that the EPA ignored peer-reviewed independent studies that link glyphosate to cancer. The agency instead used research paid for by Monsanto to support the agency’s position that glyphosate is not carcinogenic.

Dr. Charles Benbrook, a longtime friend and ally in this work, recently shared the following information.

It shines a bright light on why, after reviewing extensive U.S., Canadian and Swedish epidemiological studies on glyphosate’s human health effects, as well as research on laboratory animals, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer, or IARC, classified the chemical as “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

The concerns around this weedkiller have been ongoing for decades. A recent ruling by a jury found Monsanto guilt in August 2018 and the company was ordered to pay over $250 million in damages.

There are over 9,000 other lawsuits pending. Since the acquisition of Monsanto by Bayer, a German conglomerate, Bayer’s share price has plunged 30%.

As information continues to come out on the dishonest means by which this approval was sought, more lawsuits are sure to follow.

More from Dr. Benbrook below:

“How did the U.S. EPA and IARC reach diametrically opposed conclusions on the genotoxicity of glyphosate-based herbicides?“, Environmental Sciences Europe, January 15, 2019, DOI: 10.1186/s12302-018-0184-7.

By: Charles Benbrook, PhD

- Access paper (free)

- Access Supplemental Tables

- Access Editorial Statement “Some food for thought – A short comment on Charles Benbrook’s paper “How did the U.S. EPA and IARC reach diametrically opposed conclusions on the genotoxicity of glyphosate-based herbicides?” and its implications,” by Henner Hollert and Thomas Backhaus, DOI: 10.1186/s12302-019-0187-z

- “Why I Wrote the Glyphosate Genotoxicity Paper” — blog by Dr. Benbrook

Key Findings:

Genotoxicity studies cited in EPA’s 2016 “Glyphosate Issue Paper: Evaluation of Carcinogenic Potential” and in the glyphosate chapter of IARC’s 2017 carcinogenicity evaluation “Monograph 112: Some organophosphate insecticides and herbicides” are compared and contrasted.

Key findings are highlighted below. The graphics are available in different formats (see below).

Key Finding #1:

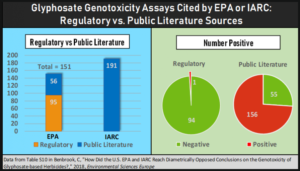

While IARC referenced only peer-reviewed studies and reports available in the public literature, EPA relied heavily on unpublished regulatory studies commissioned by pesticide manufacturers. In fact, 95 of the 151 genotoxicity assays cited in EPA’s evaluation were from registrant studies (63%), while IARC cited 100% public literature sources.

While IARC referenced only peer-reviewed studies and reports available in the public literature, EPA relied heavily on unpublished regulatory studies commissioned by pesticide manufacturers. In fact, 95 of the 151 genotoxicity assays cited in EPA’s evaluation were from registrant studies (63%), while IARC cited 100% public literature sources.

There is also a stark difference in the outcomes of registrant-sponsored assays versus those in the public literature. Of the 95 regulatory assays taken into account by EPA, only 1 reported a positive result, or just 1%. Among the total 211 published studies (right circle in the graphic), 156 reported at least one positive result, or 74%!

Key Finding #2:

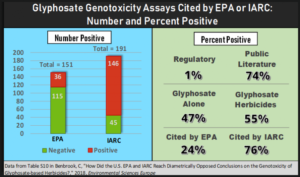

IARC, on the other hand, placed considerable weight on 85 studies focused on formulated GBHs, the herbicide people actually use and are exposed to (“Glyphosate Herbicides” in the graphic). 79% of the GBH assays published in public literature reported one or more positive result.

While EPA did list studies on formulated glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs) in an Appendix F of its report, EPA acknowledges it placed little to no weight on GBH assay results.

This difference is reflected in the overall percent of positive assays. Just 24% of the 151 assays cited by EPA reported positive results, while 76% of those cited by IARC had at least one positive result.

Key Finding #3

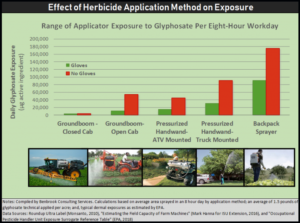

IARC’s assessment encompassed data from typical dietary, occupational, and elevated exposure scenarios. Elevated exposure events caused by spills, a leaky hose or fitting, or wind are actually common for people who apply herbicides several days a week, for several hours, as part of their work. The highest exposures typically occur when herbicides are applied with a handheld or backpack sprayer, or an ATV or truck-mounted sprayer.

The equipment used to apply GBHs has a huge impact on applicator exposures, as does whether applicators use Personal Protective Equipment like gloves. The applicator driving the modern, large-scale sprayer pictured on the left might typically spray around 500 acres in an 8-hour day, apply 700 pounds of glyphosate technical, and be exposed to 3.5 milligrams (3,500 ug, or micrograms). The applicator using a backpack sprayer without gloves would apply only about 3 pounds of glyphosate in 8 hours, but would be exposed to around 175 milligrams of glyphosate, 50-times more than the driver of the spray rig. And that driver would spray more than 230-times more glyphosate in an 8 hour day. In virtually all high-exposure scenarios, wearing gloves makes a big difference, reducing exposures by around one-half to one-tenth of “no gloves” exposure levels. The estimated exposures in the scenarios in the graphic represent applications during which everything goes “by the book,” but in the real-world a variety of factors can, and frequently do dramatically increase exposure levels.

Key Finding #4

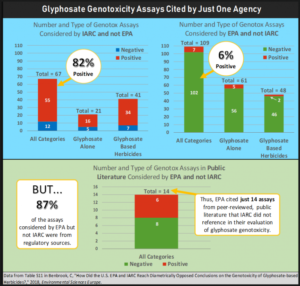

EPA cited 109 total assays not included in the IARC report, 87% of which were regulatory studies commissioned by industry, and all but one was negative.

IARC included the results from 67 assays not included in EPA’s analysis, all of which were from peer-reviewed publications, and 82% of which had at least one positive result for genotoxicity.

Graphic Files:

- Infographic of Key Finding #1 and 2

- Graphic of Key Finding #3

- Graphic of Key Finding #4

- All Graphics – .png format

- All Graphics – .pdf format

Related EPA and IARC Resources:

EPA Documents:

- “Glyphosate Issue Paper: Evaluation of Carcinogenic Potential,” EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP), September 16, 2016 (227 pages)

- ”Revised Glyphosate Issue Paper: Evaluation of Carcinogenic Potential,” EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs, December 12, 2017 (216 pages)

- “Summary of ORD [EPA Office of Research and Development] comments on OPP’s cancer assessment,” December 15, 2015 (3 pages)

IARC Documents:

- Glyphosate Section from Volume 112 of the IARC Monograph Series (92 pages)

- “Q&A on Glyphosate,” March 1, 2016 (3 pages)

- “Briefing Note for IARC Scientific and Governing Council Members Prepared by the IARC Director,” January 2018 (11 pages)

- “IARC response to criticisms of the Monographs and the glyphosate evaluation, ” Prepared by the IARC Director, January 2018

- General Q and A on the IARC Monographs

Other Resources:

- Smith et al., “Key Characteristics of Carcinogens as a Basis for Organizing Data on Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis,” Environmental Health Perspectives Vol 124(6), June 2016

- Michael Davoren and Robert Schiestl, “Glyphosate-based herbicides and cancer risk: a post-IARC decision review of potential mechanisms, policy and avenues of research,” in Carcinogenesis, October 2018

- Peter Infante et al., “IARC Monographs Program and public health under siege by corporate interests,”

- Kongtip et al., “Glyphosate and Paraquat in Maternal and Fetal Serums in Thai Women,” Journal of Agromedicine, American Journal of Industrial Medicine, April 2017

- Szepanowski et al., “Differential impact of pure glyphosate and glyphosate‑based herbicide in a model of peripheral nervous system myelination,” Acta Nueropathologica, 2018

- Santovito et al., “In vitro evaluation of genomic damage induced by glyphosate on human lymphocytes,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2018

- National Toxicology Program poster presentation on glyphosate genotoxicity, 2018

- Milic et al., “Oxidative stress, cholinesterase activity, and DNA damage in the liver, whole blood, and plasma of Wistar rats,” Archives Hig Rata Toksokol, 2018

- Sophie Richard et al., “Differential Effects of Glyphosate and Roundup on Human Placental Cells and Aromotase,” Environmental Health Perspectives Vol 113(6), 2005