The FDA and GRAS: How Food Companies Slip Additives Into Our Food

Do you know that food companies can decide for themselves which additives are safe?

It’s time to look into how new ingredients get from the food industry’s lab to your dinner table. Thousands of these additives now exist in our food supply.

Additives are added to our food to improve their texture, taste, appearance or extend their shelf life. The approval of these additives have to go through the FDA which regulates 80% of our nation’s food supply. According to the FDA, “there are thousands of ingredients used to make foods. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) maintains a list of over 3000 ingredients in its data base.”

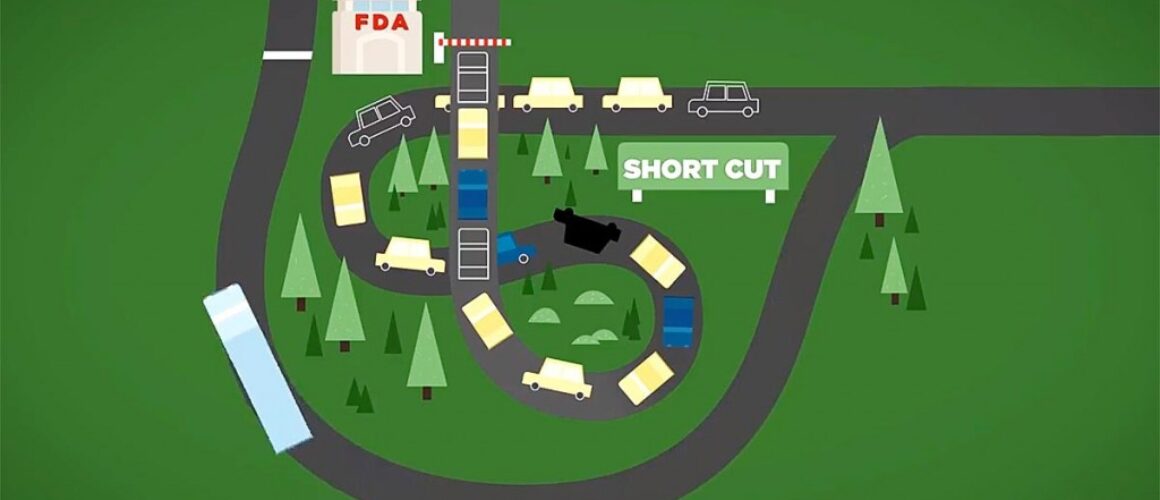

But a legal loophole exists, where ingredients that are labeled GRAS (generally recognized as safe) get a free pass through the regulatory system. It means that companies can determine on their own that what they’re adding to our food is safe. It expedites the process. Then it is up to the company to inform the FDA if they want to.

Think about that for a minute. Think about it in relation to the tobacco industry or the auto industry or any other industry. What if the car companies had the ability to determine that their products were safe without oversight?

How in the world did we let this happen?

A 1958 law allows companies to market ingredients without oversight by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration if they can establish that their ingredients are “generally recognized as safe” for specific uses. In other words, companies using the so-called GRAS process must demonstrate that there is a consensus among scientific experts that their ingredients are safe.

The Center for Public Integrity found that at least four of the top 10 GRAS panel experts had also served as scientific consultants for cigarette makers.

I’ll let that sink in for a minute, as the parallels between Big Tobacco and Big Food extend beyond the overlap of these experts.

The world of GRAS panelists is a small one. A Center for Public Integrity analysis found that the top 10 most frequently hired panelists have each sat on two dozen or more panels. Most experts have decades of experience making GRAS determinations and maintain affiliations at universities.

“These are standing panels of industry hired guns,” said Laura MacCleery, an attorney for the Center for Science in the Public Interest. “It is funding bias on steroids.”

“Funding bias on steroids.”

“It’s not a large universe of people,” said Steve Morris of the Government Accountability Office, which published a report in 2010 that cited financial conflicts of interest in the GRAS system as a concern. “The fact that there’s … repetition and there’s familiarity, that could potentially breed a conflict.”

In 2013, a Pew Charitable Trusts review of GRAS assessments concluded that “financial conflicts of interest were ubiquitous” in the system.

In 2010, the Government Accountability Office recommended that the FDA “develop a strategy to minimize the potential for conflicts of interest in companies’ GRAS determinations.”

These are not wild-eyed activist groups asking for this, but our very own Government Accountability Office.

Five years later, the FDA says it’s still working on it.

Right now, companies have no legal obligation to tell the FDA what they are putting in our food.

Think about that. Then watch this three minute clip and share this article with your family and friends.

What can we do? Tell the FDA that it’s time to stop chemical and food companies deciding for themselves that food additives are safe. Learn more here.

Learn more about Food Safety Scientists Ties to Big Tobacco here.