GMO Labeling: Are Biotech Companies Duping Their Own Shareholders?

Right now, a battle is brewing over the labeling of genetically engineered ingredients in our food. Chemical companies that make these products are fighting the labeling initiative like crazy, pouring record amounts of money into defeating any measure that would require their products to be labeled. It makes sense. Because without labels, there is no liability, traceability or accountability. In other words, they can declare there is “no evidence of harm” to their shareholders, and they’re right. Without labels, there is simply no evidence.

What is surprising is that members of the Grocery Manufacturers Association, who either label these ingredients or flat out don’t use them in the products they sell overseas, are spending their own hard earned cash to shield the chemical companies from this liability and keep customers in the dark about the industry inserting these products into our food.

Why are they doing this here in the United States while either labeling these ingredients or not using them in their products overseas? And is that in the best interest of their shareholders?

While it is obviously the fiduciary duty of the chemical companies to continue to want their products inserted into the food supply without labels, as it shields their shareholders from any liability that labeling might bring, it may not be in the best interest of the food companies, given that a growing number of consumers and farmers are now looking to avoid these ingredients in the foods they are feeding their families.

And it’s not just farmers and families that are doing this.

Companies like Target and Safeway are introducing private label brands that do not contain genetically engineered ingredients, and companies like Chipotle are labeling these ingredients and looking to build out the supply chain without them. Farmers are seeing this shift in consumer sentiment, the impact that these genetically engineered ingredients and the chemicals required to grow them are having on their farms and soil and dumping these products and shifting away from this fifteen year experiment back to less toxic methods employed by their grandfathers.

And some insiders in the chemical companies are dumping shares.

So what’s a food company to do? Continue to pour cash into measures attempting to defeat labeling efforts? Or invest in building out a supply chain that increases the availability of non genetically engineered ingredients and convert farms in order to meet consumer demand? And would it be mindful to hedge?

The answer will depend on who you listen to, as there is a duplicity at play, one that the food companies, given their fiduciary duty to their shareholders, should be mindful of.

According to the chemical companies that manufacture the genetically engineered ingredients recently introduced into our foods, these foods and ingredients are “substantially equivalent” to their conventional counterparts in the documentation provided to the FDA which has not conducted the independent studies themselves.

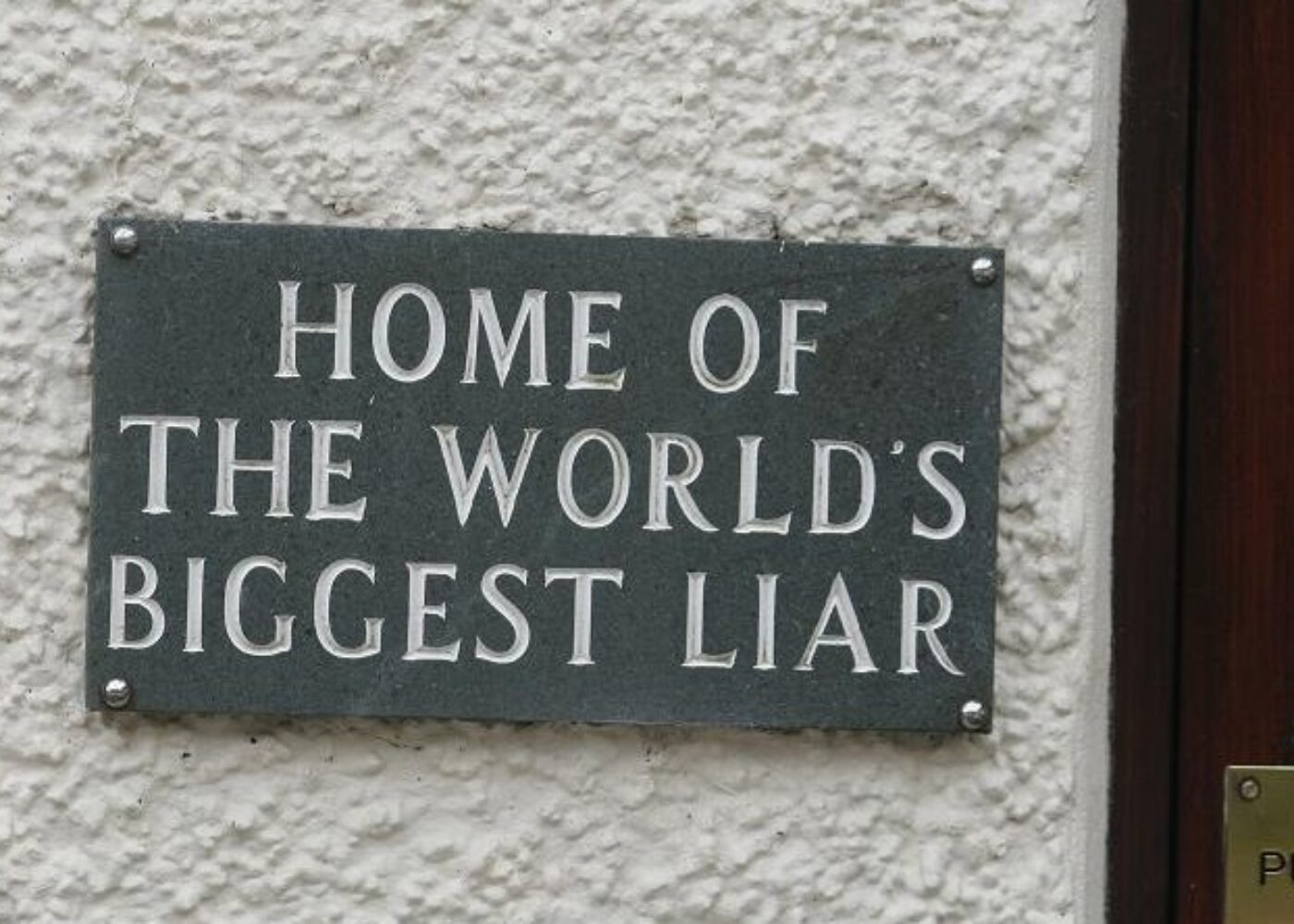

However, according to these same chemical companies, they have also told the United States Patent and Trademark Office that the novelty of these foods and ingredients are so unique that they merit unique patents on each one in order to protect the intellectual property rights and their fiduciary duty to shareholders to drive financial return. In some cases, these ingredients are so different that they are now regulated by the EPA as a pesticide.

So which is it? Substantially equivalent per the FDA or substantially different per the US Patent and Trademark Office? And how can the food companies hedge their exposure?

The FDA states: “FDA recognizes that the scientific methods to assess allergenic potential are evolving. Recent reports on the assessment of potential food allergenicity, including the allergenicity annex, have reevaluated earlier approaches and recommended some new strategies based on recent scientific opinions on this issue.”

With the jury still out, perhaps the smartest thing to do would be to opt out. A growing number of farmers want to get away from this chemically intensive operating system that genetically engineered crops require, recognizing the burden that glyphosate and other chemicals are imposing on their land and soil. On top of that, a growing number of consumers, dealing with escalating rates of diseases and conditions in their families, are moving towards clean eating.

The market opportunities are growing for the food companies if they opt out, and the ability to reduce their liabilities are, too.

Perhaps the questions that they need to ask themselves are:

Are the chemical companies telling the truth to the FDA, in which case, these ingredients are substantially equivalent enough to not merit a label? Or are they telling the truth to the US Patent and Trademark Office in which case these ingredients are substantially different enough to merit a patent?

Shareholders in the chemical and biotech companies have invested in the novelty of these ingredients and the technology that produces them. They have bet on the substantial difference, so without labels, consumers are being misled.

But if these products are substantially equivalent, as the chemical industry also claims to the FDA, then have investors in food companies been misled?

These ingredients have been patented and inserted into our food by chemical companies without our knowledge. The bottom line is that we have a right to know that, just as we know which companies make our clothes, our cars and our computers.

If you think about it, just like Intel Inside, GMOs inside our food should be labeled. If your curious what that might look like, just take a look at the way Hershey’s, one of the members of the Grocery Manufacturers Association, labels genetically engineered ingredients in the products that they sell in other countries. It’s pretty straighforward.