Finishing What We Started on Bloomberg TV about Annie’s Organic and the New Food Economy

This morning, I appeared on Bloomberg TV’s Market Makers, and the first question I was asked is: “Isn’t this Robyn against Monsanto?”

Could there be a more loaded question?

My answer: This is Robyn for a New Food Economy, for the health of our families and the health of the U.S. economy.

“What does that mean?” the host asked.

It means that we are sicker than ever before. 1 in 2 men are expected to get cancer and 1in 3 women, according to the President’s Cancer Panel. The Centers for Disease Control now reports that cancer is the leading cause of death by disease in U.S. kids, and 1 in 3 children now has autism, allergies, ADHD and asthma.

Sure, we are living longer, but with 18 cents of every dollar now spent in our economy being spent on disease management and health care, what is this costing us? As consumers, as companies, as an economy?

It’s becoming increasingly obvious that we need a new food system, one that makes clean and safe food affordable to all families, not just those in certain zip codes.

In no way is the demand for this new food system and the rise of this new food economy more obvious than in the success stories of certain brands. If you follow the share prices of Kroger, White Wave, Chipotle and Annie’s, they tell a story.

These brands are not debating science. They are not arguing against the consumer. They are simply meeting the 21st century consumer where he or she stands: in the grocery store aisles with a family member battling any one of these conditions, looking for food that is “free from” artificial ingredients.

Many things are driving this food awakening and consumers’ quest for food that is free from things like allergens, artificial dyes, high fructose corn syrup and genetically engineered ingredients.

Our country is dealing with conditions like food allergies, asthma, diabetes, obesity and cancer at rates like never before.

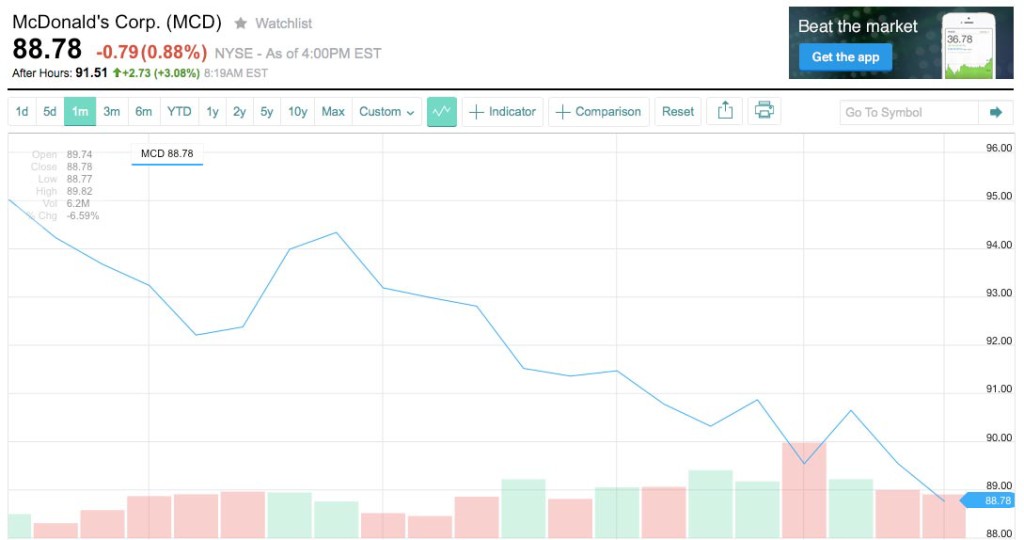

On the show this morning, we talked about how McDonald’s runs the risk of moving from a 20th century icon to a 20th century relic.19-21 year olds are abandoning the brand, the CEO just announced that he is stepping down, and same store sales are on the slide. I highlighted how Annie’s is a brand that has done an extraordinary job of meeting the needs of that 21st century consumer, and I was asked about the acquisition by General Mills, announced in 2014.

On the show this morning, we talked about how McDonald’s runs the risk of moving from a 20th century icon to a 20th century relic.19-21 year olds are abandoning the brand, the CEO just announced that he is stepping down, and same store sales are on the slide. I highlighted how Annie’s is a brand that has done an extraordinary job of meeting the needs of that 21st century consumer, and I was asked about the acquisition by General Mills, announced in 2014.

We ran out of time in the Bloomberg interview, but here are my thoughts:

When the announcement that General Mills would acquire Annie’s Homegrown was made, it sent the food world spinning.

There was an allergic reaction, and within hours of sharing the news, Annie’s Facebook page had over 9,000 comments.

To consumers, it was an emotional grenade. It still is.

As I dug into the announcement, the first email that I sent was to Annie herself, the mother who started the company 25 years ago. She quickly replied.

When Annie started the company, genetically engineered ingredients were not even in our food supply. She simply formulated a mac and cheese product for her kids that wasn’t loaded with junk.

Could she have anticipated this? Not at all.

John Foraker, Annie’s CEO, the dad of four responsible for overseeing the growth of the company and for taking it public in 2012 with one of my all time favorite ticker symbols, BNNY, also responded:

And in one swift motion, the landscape of food had changed.

No one could have anticipated food ingredients designed by chemical companies that have been genetically engineered to produce their own insecticides. Nor could the industry have anticipated this food awakening, driven by the escalating rates of diseases and conditions like cancer, autism and food allergies and other conditions impacting the health of the people that we love.

Food allergies in our children are forcing us to read labels, as quickly as cancer diagnoses are forcing the same. No one would choose to be standing in the aisles of the grocery store, holding the hand of a child with food allergies or autism or managing a parent’s cancer diagnosis, yet that is where so many of us find ourselves today. We are being forced to read labels to protect the health of our loved ones, whether we want to read them or not. And sales of organic foods are soaring, as consumers try to eat a little bit better, a little bit cleaner and opt out of artificial ingredients. The U.S. branded organic and natural foods industry’s sales have been growing at a 12 percent compound rate over the last 10 years.

And while big food companies like General Mills might have fought this for some time, they also aren’t stupid, and their job is to drive shareholder return. Sales of processed foods and conventional products that are pumped full of artificial growth hormones, artificial dyes and other artificial ingredients like GMOs are lackluster at best. The industry watches companies like Kellogg entrench and refuse to address this change in demand. What happens? Sales slump, and Kellogg is laying off 7% of their workforce.

It’s a slow death by artificial ingredients.

One look at the share price of Kroger or Chipotle tells the story of what happens to a company that expands into this ‘free from’ category: shareholders are rewarded.

Why wouldn’t a company want to enter this space in a meaningful way?

Change is hypocritical.

General Mills has been part of the anti-labeling brigade. Led by the Grocery Manufacturers Association, they have been a core member of the team of companies that have spent millions to keep consumers in the dark. When I spoke with their company recently, they were fascinated by what I had to say, then stopped and said, “But there is something on your bio that is a problem.” “What is it?” I asked. “It’s your affiliation with “Just Label It” campaign.

That is their problem, as taking the position that a consumer does not have the right to know how her food is made, despite the fact that we are told if milk is pasteurized or if orange juice comes from concentrate, is undemocratic. It’s a freedom enjoyed by 60% of the world’s population.

Annie’s has been an outspoken advocate for GMO labeling.

Consumers got on it, and General Mills was quick to reply with their position. They told consumers that we already have a way of knowing if GMOs are not in our products, and it’s called “USDA Organic.” That’s fine for consumers who can afford it, but what about everyone? For those that want to know if GMOs are used, there is no mandatory labeling system in place. Why label one and not the other? The very costs that they are arguing against, they are happily paying when they label their organic products.

So the outrage over this new marriage stems from the the fact that General Mills has fought to keep consumers from knowing what is in their products, while Annie’s has led with transparency.

The reaction that consumers are having to the announcement is the fear that General Mills wrangles Annie’s into submission. And while General Mills can operate Annie’s with an expansive economy of scale and get their price to manufacture down, it’s not all altruistic. General Mills also knows that people are willing to pay more for Annie’s products. It’s a way to diversify their portfolio, get better, higher margin products to market and increase Annie’s availability in the marketplace. It’s good for business. They also see the writing on the wall, and it doesn’t contain the letters “G-M-O.”

The fear is that Annie’s will fold, but this is where leadership and personal stories step in. Annie’s CEO, a dad of four who comes from a farming family, holds a degree is in agricultural economics and has a background in banking, will be a pivotal leader in the organization. He knows the supply chain and knows the demands of the financial world. He also knows what it is like to see someone that you love face serious health challenges. He knows that families around the country are experiencing these challenges every day.

And like the CEO of Stonyfield did when he expanded the brand and the reach of the yogurt company through its Danone partnership, Annie’s CEO found a partner to expand and capture economies of scale that the company couldn’t on its own. Stonyfield’s founder never backed down.

General Mills buying into the organic movement through the purchase of Annie’s provides distribution and access to capital.

Is consolidation the best answer? “These big food companies aren’t going to let anything else happen,” said one of the portfolio managers that I used to work with when I spoke with him today.

And right now, our food system is currently structured in a way that the costs of production for organic ingredients are disproportionately higher. It is structured this way at the federal level. It is not a level playing field for the organic industry. And when a company goes public, the way that Annie’s did in 2012, it is opening itself for an acquisition.

Does it mean that it will always be this way? That policy will always be this way? Not at all. Policy follows the money, and right now, the organic industry is growing while conventional is stagnant. The landscape of the food industry is changing at every level. Amazon is entering the retail space, online distribution companies are entering, too. Farmers market and community supported agriculture are taking off. Why? Because the grocery retail structure makes it hard for smaller brands to compete. They either have to sell out or buy in. It requires capital.

To hit the scale and scope of distribution that makes a product accessible and affordable to all Americans, companies have repeatedly sold themselves to a larger company: Stonyfield to Danone, White Wave to Dean Foods, Happy Family again to Danone. The list goes on.

Have these brands sold out? Or have the bigger brands bought into the organic movement? Stonyfield didn’t sell out. Happy Family didn’t either. Both companies were founded by people who have personally known how autism or cancer can impact a family.

Do I wish there were other ways for these companies to scale? And that the food industry had a level playing field for organic companies? Absolutely. There is nothing that I would rather have seen then Annie’s, White Wave, Hain Celestial and other organic brands become the iconic brands of the 21st century. Our generation’s iterations of Kraft, General Mills and Pepsi.

Perhaps this is the first iteration towards that. But right now the cost structure is prohibitive. We haven’t financed a healthy food system at the federal level. If farmers want to grow organic crops, they lose the crop insurance protection programs, they lose subsidies and they lose marketing support. Is that financially viable?

The food movement is not going away. Demand for food that is ‘free from’ artificial ingredients like food dyes, GMOs, high fructose corn syrup and other ingredients is not a fad, because cancer, autism and food allergies are not fads. We are seeing a fundamental shift in the way that Americans buy food, because we are sick.

General Mills obviously recognizes that. They are hedging with this acquisition, balancing their portfolio. The key is to not compromise the integrity of the Annie’s brand in the process. Creative destruction is an economic term trumpeted by a man named Joseph Schumpeter. And change, in these early stages, often looks like hypocrisy. It often looks destructive. The question becomes: what is the long term objective here? Is it really to destroy a brand? No, it’s to capture its market share, its margins and expand into the category.

So how could this play out?

A look back at other historic acquisitions in the food industry gives us a feel for how this could play out, because if the share prices of White Wave and other organic companies are any indication today, this consolidation stage will continue.

In 1985, Philip Morris Cos. became a holding company and the parent of Philip Morris Inc. and bought General Foods. The acquisition of Kraft Foods came in 1988. In 2001, Kraft Foods spun out of Phillip Morris and launched an IPO for 11.1% of the company that raked in $8.7 billion, making it the 2nd largest IPO in American history at the time

If General Mills decides to grow the Annie’s brand and then spin it out again in a few years time, like Philip Morris did with Kraft or like Dean Foods did with White Wave, they would drive enormous shareholder value if they stay true to the brand.

If they don’t, there are plenty of examples of fallout in the food industry. From Kellogg’s, to the companies that made pink slime to those that put yoga mat material in their buns. Shareholders suffer if companies don’t response to the 21st century online consumer.

We live in a day and time where online bullying can take many forms. At the end of the day, no one misses a beat, and companies that think they can pull a fast one on the consumer are quickly proven wrong.

Refinance Food

We have financed a food system that gives food companies the incentive to use the cheaper ingredients. The cost of producing organic ingredients is disproportionately higher than producing conventional, genetically engineered crops. On top of that, farmers that choose to grow organic crops don’t get the crop insurance programs and marketing support programs. In other words, their entire cost of production is higher. That hammers all of us. It hammers food companies trying to do the right thing.

And as much as any of us want to romanticize food, right now, this is our current capitalist structure, and until we refinance the food system, this won’t be the first of these acquisitions.

What if the cost of production were the same? What if farmers, regardless of what they choose to plant on their farms, could receive crop insurance programs and marketing support? What if food companies, regardless of what they choose to use in their products, had to label their ingredients as genetically engineered or not.

Right now, there is economic discrimination. Costs are disproportionately higher for those who want organic food, from the farmers growing it to the food companies using it to the families eating it.

Does anyone want it this way? Does General Mills? Do our farmers? Do our families?

But we weren’t given a choice.

Right now, our taxpayer resources are used to support the food system dependent on GMOs and chemicals. What if at the voting booth, we got to check a box?

Do you want your taxpayer resources to support the food system? And if yes, which would you rather see support given to farmers growing organic ingredients? To food companies using them?

How do we want our tax dollars to work in the food system?

What would General Mills choose if price weren’t an issue? If there were an economic equilibrium, which ingredients would General Mills choose? Genetically engineered or organic? And why haven’t we structured our food system with this kind of pricing parity?

Right now, no one has been given the choice because of the financial structure executed at the federal level through the crop subsidy programs, the crop insurance programs and the marketing support programs. They only go one way.

Is this acquisition a symptom of that unhealthy financial structure?

Under terms of the agreement, General Mills will acquire Annie’s for $46.00 per share in cash. The proposed transaction has an aggregate value of approximately $820 million.

It’s not a hostile takeover. Annie’s entered into it as a way to grow to reach more consumers, just like Stonyfield did with Danone or White Wave did with Dean Foods.

The question is whose compass is stronger? What will consumers do to send the message to General Mills that being part of the anti-labeling campaign is detrimental to shareholders?

Annie’s has the wind at its back. General Mills know that. Consumers want “free from” food. Food that is “free from” artificial ingredients, artificial dyes, growth hormones and genetically engineered ingredients. One look at the share price of Chipotle tells that story.

As more and more companies enter the organic space, either through new products or through acquisitions, it again begs the question: is the Grocery Manufacturers Association a relic of the 20th century? If this organization is not working to meet the needs of its member companies, should it still exist in its current form? Or should a new organization, let’s call it the Food Production Association, be formed to meet the evolving needs of these brands in the 21st century?

Change at its very core begins with hypocrisy.

If General Mills chooses to make a strategic shift and follow Annie’s into an industry with a 12% compound annual growth rate, delivering a portfolio increasing full of “free from” foods, shareholders will be rewarded. The rates of cancer, autism, food allergies and other conditions aren’t declining. This food awakening isn’t a fad.

Annie’s has the potential to be a powerful compass for General Mills. If the companies are serious about their commitment to the 21st century consumer and their shareholders, they should step away from the Grocery Manufacturers Association’s anti-labeling campaign and join the consumer where she stands: in the grocery store aisles, reading food labels while holding the hand of a loved one with allergies, autism, EoE, cancer, diabetes or any one of the conditions impacting our families today and deliver exactly what she wants: food that is “free from” artificial ingredients and information about how she can protect the health of her family.

General Mills is already labeling genetically engineered ingredients in the products that they sell overseas, or they’re not using them altogether.

It’s up to them if they continue to operate with a 20th century mentality or if they will move into the 21st century with the consumer and Annie’s as a compass.

Kellogg has a story to tell. Chipotle does, too.

It’s up to General Mills which one will be theirs. And if their shareholders are paying attention, the writing is on the wall, and it doesn’t contain the letters “G-M-O.”

Note: I do not own shares in any of these companies.