A Meaty Problem for the Food Industry: Organic Demand

I was on a call this morning with Applegate’s team, listening to the founder talk about his decision to sell the company to Hormel.

He spoke, as most founders do, of the personal story that inspired him into the business, of the near failure of the company and of his passion to persevere. He also spoke about the stroke that he had a few years ago that forced him to consider his leadership position and his struggle to find a replacement.

It takes a certain type of person to pioneer, and as he spoke about his decision to sell Applegate to Hormel for $775 million, I found myself wishing once again that we had financed a smarter food system.

What we call “organic,” other countries call “food”. Overseas, they label the new ingredients, the GMOs, the artificial growth hormones. In the U.S., we use the adjective “organic” to describe food that is free from these artificial ingredients. Pioneers like Stephen have fought for it.

The companies that are willing to be transparent in the U.S., to keep their products as clean and free-from artificial ingredients as possible, are the ones that earned the trust of a generation of parents. Most of those companies are in the organic space. I had no idea what “organic” meant at the time and dismissed it as a marketing gimmick, but I quickly learned that according to the USDA, by law, organic products are products that are produced without the use of artificial growth hormones, artificial dyes, sewage sludge, genetically engineered ingredients and the synthetic pesticides routinely sprayed on them.

In other words, food that is free-from certain artificial ingredients.

As I looked at the food industry that I’d once covered as an analyst, I saw both sides: organic and conventional. It was as divisive as any religious belief. On one side were the brands that we’d been raised on. We trusted them the way we trusted our own moms, our families that had used them. On the other side were brands we’d never heard of. Were they safe? Did they taste good? Could we trust them?

As that began to happen, and the organic industry began to grow: I looked at the two sides again and could see a very dividing line: on the one side were brands of the 20th century, built out of a food system defined in the 1970s and 1980s. On the other side were 21st century brands, companies that had grown into their own as we did, while the landscape of the health of our families changed.

In 2014, sales of organic food and non-food products in the United States broke through a record, totaling $39.1 billion, up 11.3 percent from the previous year. Organic sales are now near a milestone 5 percent share of the total food market. But that is still only 5% of a massive industry, and it made me step back. We don’t have enough farmland under organic management to meet this demand. We are outsourcing the opportunity to other countries.

If we are truly going to change the food system, we have to acknowledge that the organic industry needs a stronger supply chain. 1% of farmland doesn’t meet the needs of the 5% share of the total food market. We have to recognize the risks that this presents, as well as the returns.

An industry that has a 5% share of the total food industry also means that the organic industry wide open and vulnerable to acquisition.

How so? The entire organic industry has a market capitalization of $39 billion. By comparison, the market cap of PepsiCo is $141.4 billion. The market cap of Coca Cola is $178.7 billion. Together, the market caps of Coca Cola and PepsiCo alone are ten times the size of the organic industry.

In others words, as much as the biotech industry would love to have everyone believe that there is a problem with “big organic” it is a misnomer, as the entire organic industry could be acquired by big soda.

With the announcement of Applegate’s acquisition by Hormel for $775 million, shares of White Wave started moving again on rumors that Coca Cola would acquire it. It would make sense. Coca Cola missed the opportunity to build out this section of their portfolio, so the fastest way to buy into the growth is through acquisition.

It’s not surprising, and it’s not unprecedented. When a seven or eight hundred million dollar offer is put on the table as it was with Annie’s and Applegate, it is hard to turn away, as that capital infusion represents access to growth, economies of scale and other ways to reach more consumers. Nowhere else is there access to that kind of capital for these companies at that cost.

In a perfect world, where there is an economic equilibrium between the production costs of organic and conventional, the goal would be to have companies like Hormel buy in without companies like Applegate selling out. But given the capital structure of our food system, it is increasingly tough.

We’ve financed a chemically intensive food system, built on genetically engineered crops designed to withstand increasing doses of weedkillers that the World Health Organization now deems “probably carcinogenic.” In other words, we’ve financed a food system with government subsidies that may cause cancer, while charging organic food companies and farmers fees to prove that their products are safe. It’s like getting fined to wear your seatbelt. On top of that, an IPO is more expensive than an acquisition: banks are paid fees to structure, shop and process the deal. As Applegate considered its next move, to IPO or to sell, the financials favored the sale because it is less expensive than the IPO in the short term.

But what about the long-term?

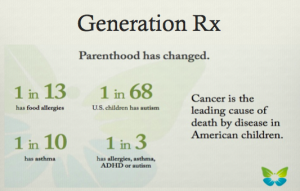

We’re staring down a barrel when it comes to our health. Ask anyone at work, on the sidelines of a soccer game or at the next classroom event what their health concerns are in their families, and they will have a list. Cancer, diabetes, autism, food allergies don’t care what side of the aisle we are on or where we land on the socio economic ladder. They steal people that we love regardless.

The beauty of the 21st century is that we have technology and tools that have never existed before, and using innovation, strategy and creativity, we can design a smarter food system, a smarter capital system, a more efficient IPO process.

To build a better food system is critical for the health of our economy, our competitiveness in the global marketplace and for our families.

Did anyone expect to create value in the industry so that Hormel and others could come in and capitalize on it through acquisitions? Some did, but not everyone.

Companies like Hampton Creek are building an entirely different model, declining offers and looking towards an IPO process that allows stakeholders to buy in. It’s happening across the food system, from fast food restaurants like Lyfe Kitchen to those in the supply chain.

Companies like Target, Kroger, Similac, Panera, Taco Bell and even Pizza Hut are dumping ingredients that the FDA has told us are “generally” safe. In one day, Similac baby formula and Hellmann’s mayonnaise announced that they are launching GMO-free products, Jelly Belly announced they are launching organic jelly beans, and Taco Bell and Pizza Hut announced that they are dumping artificial ingredients, ingredients that the FDA has said are “generally” safe. So what purpose does that agency now serve if consumers and food companies are moving past it? Is it underfunded, overcommitted, sold to the highest bidder or simply broken? Should we have a food agency that is separate from the drug agencies like other countries?

There is a lot of work to be done. And it can’t happen quickly enough. With just 1% of U.S. farmland dedicated to organic farming, the industry is going to choke on its own growth if it doesn’t address supply constraints and capacity. An organic check-off program would begin to address is, but a reboot and refinancing of the entire system is needed.

Many believed that if we threw ourselves into this work to create a better food system, that 21st century iconic brands would replace the relic brands of the 20th century. The founders of Applegate and Annie’s believed it, just as the founders of the iconic 21st century brands do.

I truly believe that it will still happen and that this period of consolidation will be followed by a period in which these companies are either spun back out or in which they reinvent those that are acquiring them. And there will be a few that will be willing to go it alone, despite the jeers, the naysayers and non-believers, just as Apple did in the tech world and Tesla in the automotive industry, and there success, no doubt, will be enormous.

78 percent of organic buyers say they typically buy their organic foods at conventional food stores/supermarkets. Over half also shop organic at the “big box” stores, and some 30 percent also report that it’s not unusual to buy organic at one of the warehouse clubs in the country.

African American and Hispanic families have been steadily increasing among the ranks of organic-buying households.

Organic is not a fad because caring for the health of our families isn’t one either.

The health of our country depends on a healthy food system.

But right now, as new companies get started, we are in an intense stage of consolidation. Food allergy families have trusted some of these brands like Enjoy Life Foods with the lives of their children. Cancer families have done the same. The statistics driving this food awakening are powerful. They are not a trend: cancer is the leading cause of death by disease in U.S. kids and now impacts 1 in 2 men here and 1 in 3 women; a food allergic reaction sends someone to the emergency room once every three minutes in the United States.

The financial cards are stacked against the companies trying to deliver free-from food, “organic” if you want to use that adjective. Nothing is impossible, as Nature’s Path and Amy’s are fighting to prove, but it’s hard. It’s not impossible, again, just look to Apple.

But what will be harder is to look into the eyes of our kids when they ask what we did to build a better food system.

It is an all hands on deck time. The leadership teams of General Mills and Kraft are not immune to the conditions hammering our families and our country.

As these acquisitions continue, these smaller brands can serve as a compass inside the larger ones. The differences in cultures are great, but courage is contagious. The string of announcements over the last few weeks of food companies dumping the junk shows just that: from Panera, Kroger, to Target, Taco Bell and Pizza Hut, the desire for food that is free-from junk is no more of a fad than cancer is. They are not ignoring the science, they are responding to calls for more science, more evidence and more precaution in light of the escalating rates of diseases in our families. They are responding to the changing demands of the 21st century family.

Until we refinance the system, consolidation will continue. Market caps will be lost and gained by those that choose to do the right thing.

The divide between organic food brands and conventional ones may be deep. With the health of our country resting squarely on our shoulders, we have a choice: to make a bigger mess of our food system or to build a legacy.

As I listened to the founder of Applegate on the call, he spoke about scaling, because “it’s a decision to do something right.”

Can it be done by Applegate and others?

His response: “a resounding yes,” and then candidly, he said, “It is not without risk.”

Nothing worth doing ever has been without risk. It is an all hands on deck time. The organic industry is growing, perhaps not in the way that we might have imagined, but it is growing. To jump ship now concedes defeat. Now is the time to measure and manage the changes in the organic industry, to uphold standards and to create new ones.

The opportunity in front of us is enormous: 95% of the food industry.

The legacy of a better food system is ours to create.